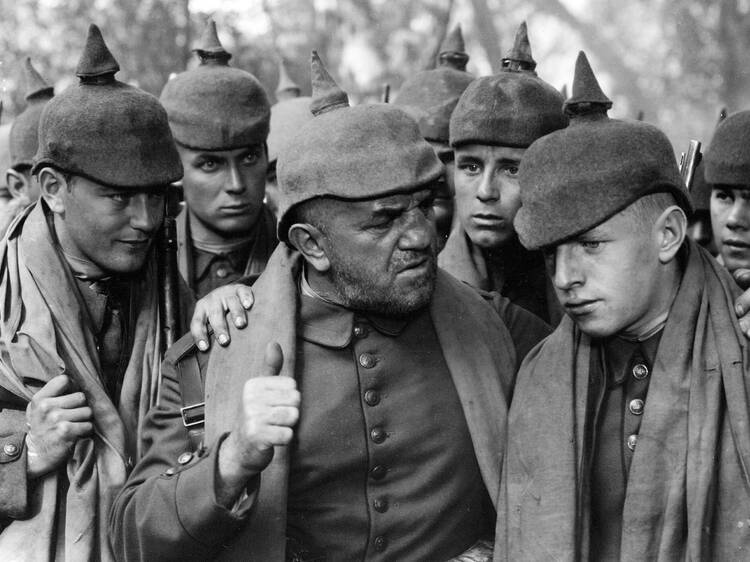

Not just a violent crucible but also a petri dish for technological, medical and social leaps, the First World War is still indirectly fuelling innovation a century later. Peter Jackson’s sui generis documentary joins 1917 in reinventing the grammar of war films, painstakingly colourising reams of archive footage and adding the sounds of the war – including the actual voices of veterans – to create a truly haunting immediacy. Hearing some of the soldiers recalling their sadness when the Armistice finally came is a useful reminder that the experience of war was far from homogeneous.

The expert view: ‘It’s an incredible film in the way it brings the archives to life and it’s so powerful for featuring the recordings of the veterans. It shocked me to the core to hear the voices of men who’d been dead for 30 years that I’d once interviewed. Anyone with even a passing interest in the war should see it.’